Editor's Choice

The Children's Literature and Culture team pick some of their highlights from the resource.

McLoughlin Bros. and the Commerciality of Christmas

Steven Edwards

One of the absolute joys of working on Children’s Literature and Culture has been the opportunity to lose oneself within its ‘embarrassment of riches’. A moment’s pause amongst the more visually stunning documents in the resource is hard to resist whenever their eye-popping colours or dreamy, pre-Raphaelite inspired moods catch the eye.

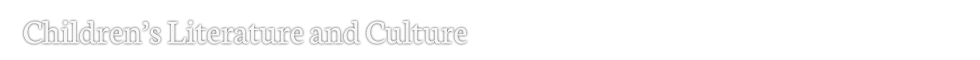

Prominent within this colourful cavalcade of material are the publications of the McLoughlin Brothers of New York, brought to life, as they are, by their fanciful designs and the vibrancy of the colour lithographic printing techniques employed to produce them. McLoughlin was, arguably, the foremost American publisher of children’s books in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but the company was also a leading maker of toys and games for children. Games from this era are scarce, largely because of the ‘enthusiastic’ treatment they received at the hands of their youthful owners and the consequent low survival rate, but a charming selection of McLoughlin products is included within this resource.  As you might expect from a company of people who became such masters of their art, the colour images which adorned McLoughlin games were every bit the equals of those found between the covers of their books. Box covers featured beautiful chromolithographs and lithographic illustrations which raised the bar for the marketplace and set McLoughlin apart from its competitors. Almost everything that bore the McLoughlin name – from cube blocks (as in Little Folks Cubes: The Babes in the Wood), jigsaw puzzles (as in A New Dissected Map of the United States) and spelling games (as in Sliced Animals Improved) to tangrams (as in Chinese Puzzle), card games (Where's Johnny), panoramas (Uncle Sam’s Panorama of Rip Van Winkle) and even fortune-telling games (such as Chiromagica) – featured the characteristically gorgeous artwork made possible by the company’s systematic and pioneering use of colour printing technologies.

As you might expect from a company of people who became such masters of their art, the colour images which adorned McLoughlin games were every bit the equals of those found between the covers of their books. Box covers featured beautiful chromolithographs and lithographic illustrations which raised the bar for the marketplace and set McLoughlin apart from its competitors. Almost everything that bore the McLoughlin name – from cube blocks (as in Little Folks Cubes: The Babes in the Wood), jigsaw puzzles (as in A New Dissected Map of the United States) and spelling games (as in Sliced Animals Improved) to tangrams (as in Chinese Puzzle), card games (Where's Johnny), panoramas (Uncle Sam’s Panorama of Rip Van Winkle) and even fortune-telling games (such as Chiromagica) – featured the characteristically gorgeous artwork made possible by the company’s systematic and pioneering use of colour printing technologies.

It is, I find, as much for their beauty and scarcity as for their entertainment value that these games hold such appeal. Amongst the many personal highlights is Game of the Visit of Santa Claus, issued by McLoughlin in 1897. Whilst sitting down in front of a roaring log fire to enjoy this festive board game, its young players would send Santa on his epic, once-yearly trip around the world (or, at least, around the board) in his sleigh. The aim of the game was for Santa to stop at your home whilst passing by those of your opponents so that you might gather the most gifts from the man in red so beautifully illustrated on the box cover. Gifts were represented by cards bearing such temptations as marbles, fire engines and tin trumpets, and whomever collected the most cards duly won the game.

As straightforwardly innocent as this festive-themed children’s game might at first seem, it was but one manifestation of McLoughlin’s astute appreciation of the increasing commerciality of Christmas and the keen eye for the marketplace which lay behind it.

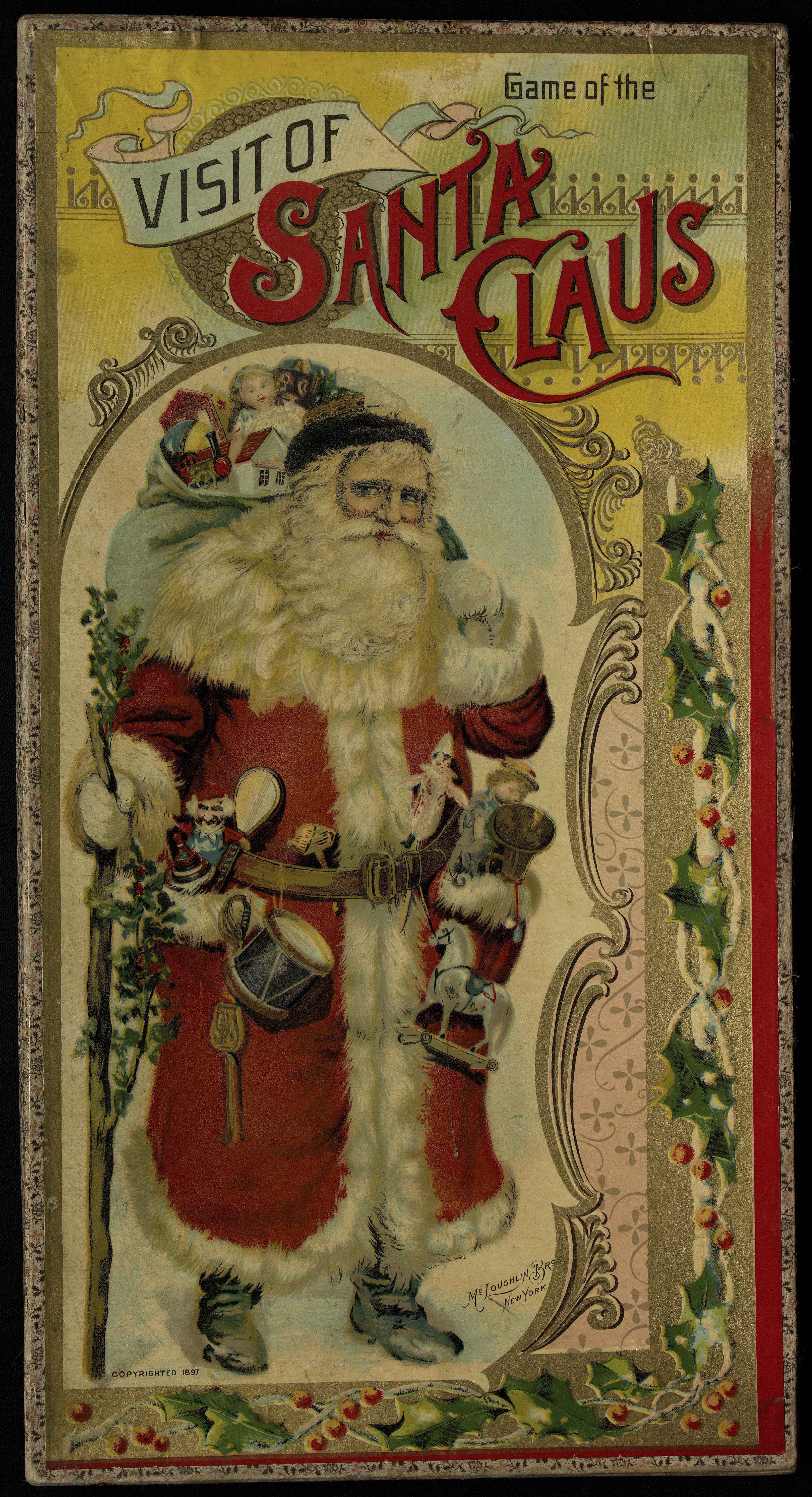

As the nineteenth century wore on, Christmas gradually came to replace New Year’s Day as the predominant winter celebration. Simultaneously, it became less religious, more commercial. Publishers had long understood that children’s books made wonderful gifts and, accordingly, they would release slews of new titles in good time for the holiday season. McLoughlin was no exception but, as in so many other ways, the company was ahead of the curve.  In 1869, McLoughlin issued one of its earliest seasonal publications – a picture book version of Clement C. Moore’s A Visit From St Nicholas (more commonly known as The Night Before Christmas and first published back in 1823). To add visuals to Moore’s classic poem the company hired the experienced hand of political cartoonist extraordinaire, Thomas Nast. Since the early 1860s, in his role as a staff illustrator at the magazine, Harper’s Weekly, Nast had been developing his vision of Moore’s idea of Santa Claus as “a right jolly old elf”, conceiving of a merry, heavyset, fur-suited Santa and gradually introducing to the world the modern image that we know and cherish. McLoughlin quickly appreciated the visual marketing appeal of Nast’s Santa and, by hiring Nast, clearly demonstrated its business acumen and marketing savvy.

In 1869, McLoughlin issued one of its earliest seasonal publications – a picture book version of Clement C. Moore’s A Visit From St Nicholas (more commonly known as The Night Before Christmas and first published back in 1823). To add visuals to Moore’s classic poem the company hired the experienced hand of political cartoonist extraordinaire, Thomas Nast. Since the early 1860s, in his role as a staff illustrator at the magazine, Harper’s Weekly, Nast had been developing his vision of Moore’s idea of Santa Claus as “a right jolly old elf”, conceiving of a merry, heavyset, fur-suited Santa and gradually introducing to the world the modern image that we know and cherish. McLoughlin quickly appreciated the visual marketing appeal of Nast’s Santa and, by hiring Nast, clearly demonstrated its business acumen and marketing savvy.

The popularity (which endured for more than a decade) of McLoughlin's 1869 printing of A Visit From St Nicholas made it highly likely that Santa would reappear the following year – and not just high above, in darkened skies, on Christmas Eve. Sure enough, the company continued its investment in Nast’s Santa for years to come, popularising him not just in books but through Christmas-themed blocks and puzzles and, indeed, products such as Game of the Visit of Santa Claus. The raving success of these products played a significant role in the lasting shift of emphasis from New Year’s Day to Christmas and, as the consumerism of the holiday kept growing, McLoughlin continued both to service and capitalise upon it with countless books, games and toys, many of which remained centered around Nast's enduring image of Santa Claus. In doing so, the company cemented its impact upon the festive season in both America and the wider world.

More books and games on these subjects can be found under the Calendar Events and Holidays and Leisure and Play themes.

Depictions of Physical Disability

Corinne Clark

In 1817, Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet founded the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, originally known as the “Connecticut Asylum for the Education of Deaf and Dumb Persons”. Although not the first school of its kind to be founded – an institute in Virginia was established in 1815, but had closed by late 1816 – it was the first school of primary and secondary education to receive aid from the federal government, and it successfully went on to receive and educate students with visual, hearing and speech impairments.

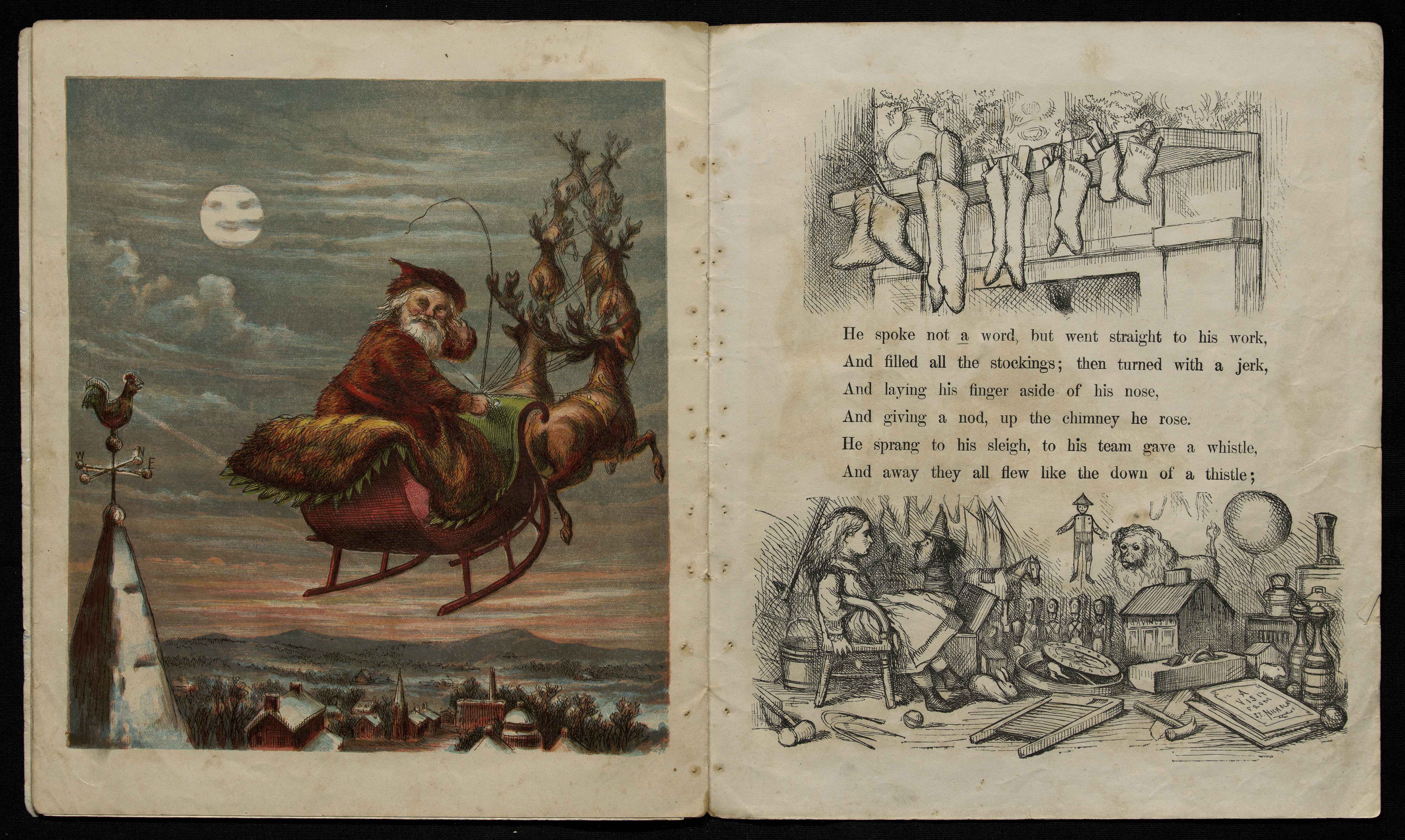

The Manual Alphabet, Used by the Deaf and Dumb is a pamphlet within the collection which demonstrates nineteenth century society’s growing engagement with the disabled community. The pamphlet features visual representations of “the manual alphabet” (a developing variation of French Sign Language), intended for educational use by children without disabilities. Below the illustrations of the alphabet, it recounts the experience of two children with disabilities, Julia Brace and Laura Bridgman. Julia Brace enrolled at the American School for the Deaf in 1825 and learned sign language, the only student at the school during that time with a visual disability in addition to a hearing impairment. Laura Bridgman, born several decades later, lost her hearing, sight, and sense of smell after contracting scarlet fever. Bridgman was a student at the Perkins School for the Blind and was one of the earliest deaf-blind Americans to achieve significant and sophisticated education in the English language. Charles Dickens met Bridgman on his 1842 tour of America, and his detailing of Bridgman’s experiences in his American Notes raised awareness of the growing possibilities for those with disabilities. Forty years later, Bridgman’s success would inspire Helen Keller’s mother to seek out specialist instruction for her daughter, initiating Helen Keller’s education and future career as an author, political activist, and lecturer.

The Manual Alphabet, Used by the Deaf and Dumb is a pamphlet within the collection which demonstrates nineteenth century society’s growing engagement with the disabled community. The pamphlet features visual representations of “the manual alphabet” (a developing variation of French Sign Language), intended for educational use by children without disabilities. Below the illustrations of the alphabet, it recounts the experience of two children with disabilities, Julia Brace and Laura Bridgman. Julia Brace enrolled at the American School for the Deaf in 1825 and learned sign language, the only student at the school during that time with a visual disability in addition to a hearing impairment. Laura Bridgman, born several decades later, lost her hearing, sight, and sense of smell after contracting scarlet fever. Bridgman was a student at the Perkins School for the Blind and was one of the earliest deaf-blind Americans to achieve significant and sophisticated education in the English language. Charles Dickens met Bridgman on his 1842 tour of America, and his detailing of Bridgman’s experiences in his American Notes raised awareness of the growing possibilities for those with disabilities. Forty years later, Bridgman’s success would inspire Helen Keller’s mother to seek out specialist instruction for her daughter, initiating Helen Keller’s education and future career as an author, political activist, and lecturer.

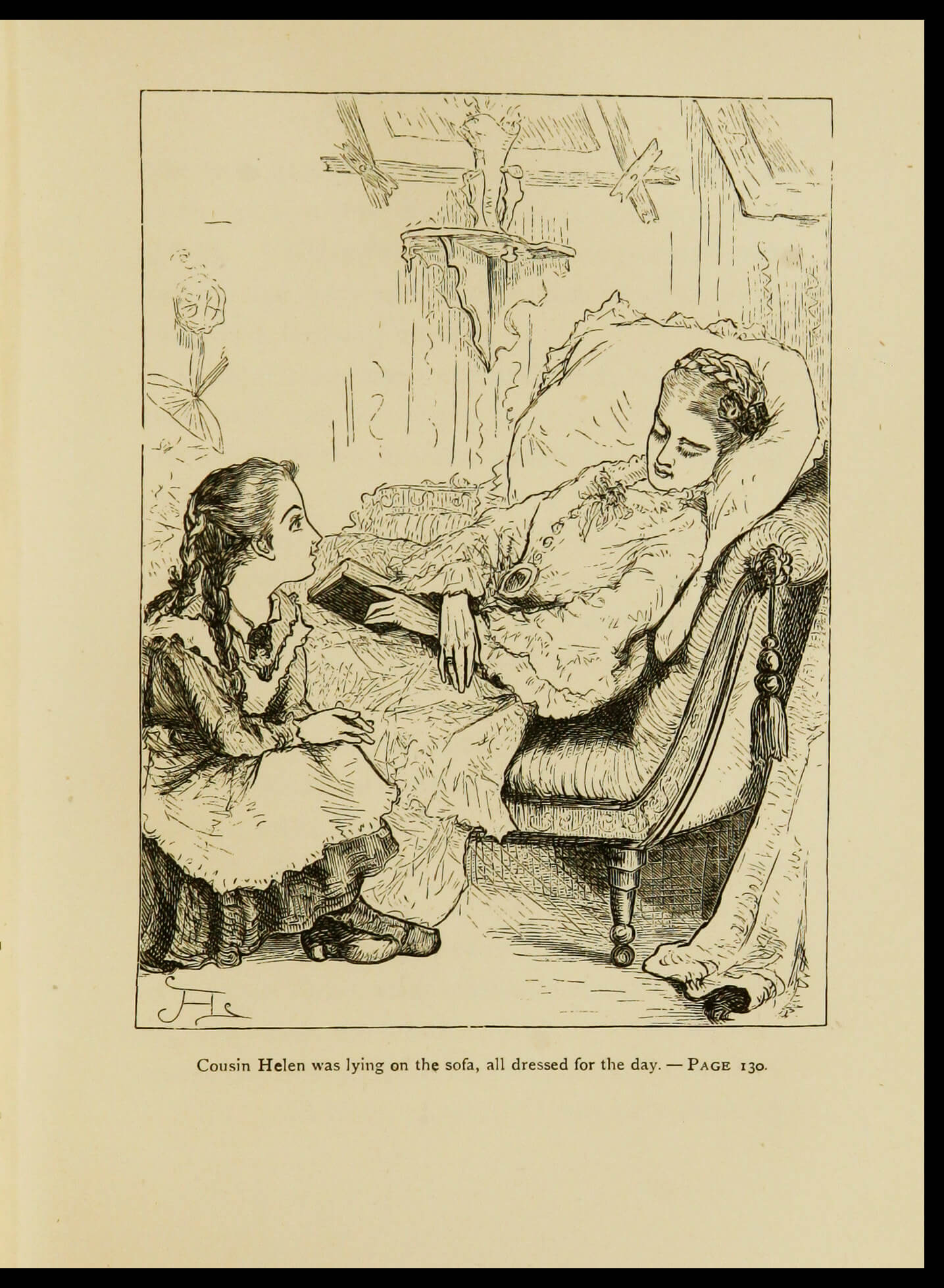

The real-life achievements of people with disabilities in a century which saw the development of Braille and the foundation of many academic institutions geared towards their education are, frustratingly, rarely reflected in their literary depictions, many of which can be explored within the Children’s Literature and Culture collection. In texts like What Katy Did (1872) by Susan Coolidge, disability is depicted as a consequence of misbehaviour – Katy’s accident occurs after disobeying her guardians’ instructions not to play on a swing – or a means by which they may demonstrate their ‘inner goodness’, as with Cousin Helen. What Katy Did is also exemplary of the most common difference between depictions of girls with disabilities and boys with disabilities. Whilst both are invariably encouraged to learn and grow through discipline and suffering, the emphasis is on the boys’ development and demonstration of courage in an assertion of independence and a degree of control over their circumstances, whereas the narrative of disability experienced by girls and women emphasises their journey towards becoming more useful to their families and the suppression their independent desires and activities.

Coolidge does address some of the prevailing literary trends through Katy’s own preconceptions of the “saintly invalid” in an intradiegetic reference to a novel published in 1815, The History Of Lucy Clare, written by Mary Martha Sherwood. Before Helen’s arrival, the children speculate on her appearance and behaviour, deciding that she will be "something like 'Lucy' in Mrs. Sherwood […] she’ll keep her hands clasped so all the time, and wear ‘frilled wrappers,’ and lie on the sofa perfectly still, and never smile, but just look patient”. Instead, they are surprised by Helen’s humour and ordinary demeanour and clothing:

Coolidge does address some of the prevailing literary trends through Katy’s own preconceptions of the “saintly invalid” in an intradiegetic reference to a novel published in 1815, The History Of Lucy Clare, written by Mary Martha Sherwood. Before Helen’s arrival, the children speculate on her appearance and behaviour, deciding that she will be "something like 'Lucy' in Mrs. Sherwood […] she’ll keep her hands clasped so all the time, and wear ‘frilled wrappers,’ and lie on the sofa perfectly still, and never smile, but just look patient”. Instead, they are surprised by Helen’s humour and ordinary demeanour and clothing:

“She looks just like other people, don’t she?” whispered Cecy, who had come over to have a peep at the new arrival.

“Y-e-s,” replied Katy, doubtfully, “only a great, great deal prettier.”

Disability is still, however, treated as a curiosity, and Cousin Helen’s ability to look ‘just like ordinary people’ goes hand-in hand with her determination to conceal her pain from those around her. Visible disability is viewed either as an object of pity, as with the character of Bessie in Carrie Hamilton; Or, the Beauty of True Religion, or as something to be concealed and endured in silence as much as possible as a mark of good character. Cousin Helen's advice that Katy make herself the “heart of the house”, encourages the marginalisation of Katy’s own life as a result of her disability: “when one’s own life is laid aside for a while, as yours is now, that is the very time to take up other people’s lives, as we can’t do when we are scurrying and bustling over our own affairs”. As the ‘heart’ of her family, Katy is encouraged to provide a vacuum of herself which others without disabilities may fill with their own lives and emotions.

Despite the steps towards independence being taken by real-life women with disabilities like Laura Bridgman and Helen Keller, literary representations remained problematically restricted to narratives which suppressed the assertion of individuality and autonomy of the disabled community.

More texts on this subject can be found in the documents under the Disability theme.

Mother Goose: Reception and Perceptions

Alexander Barr

Children’s Literature and Culture contains a great number of Mother Goose books, spanning many different editions, titles and reproductions. Originating as a collection of fairy tales published by Charles Perrault in 1697 and brought into English in the 18th century, Mother Goose evolved into the form typically found in Children’s Literature and Culture: anthologies of popular nursery rhymes and lullabies often accompanied by vibrant, eye-catching illustrations. These Mother Goose books offer an interesting insight into how books and reading were received and perceived among contemporary society.

The formula for Mother Goose books was a winning one, and the books were received to great acclaim. If the sheer volume and variety of Mother Goose books in Children’s Literature and Culture is not sufficient evidence for their popularity and success, it is further emphasised by the books themselves. The preface to Mother Goose's Melodies, With New Pictures (c.1866) compares Mother Goose to Shakespeare: ‘all imitators of my refreshing songs might as well write a new Billy Shakespeare as another Mother Goose: we two great poets were born together, and we shall go out of the world together!’

Despite their apparent success, there seems to have been some debate on how fit the Mother Goose books were for children. While Mother Goose's House Party (1890) espouses their ability to ‘serve as intellectual food for the awakening mind of the child’, Jack Halyard and Ishmael Bardus (1828) dismisses the nursery rhymes as ‘trash’ and ‘falsehoods’. One book, Songs for my Children: With Numerous Illustrations (c.1861), sought to supersede Mother Goose entirely with poems ‘grave enough to instruct and profit’. The editors of Melodies for Children or Songs for the Nursery (1878) felt the need to defend the worthiness of their book against the Mr Gradgrind, the Dickensian school board superintendent who would ‘censure him for his indifference to the realities and facts and calculations which are the proper pabulum of the infant mind’. Such comments offer an insightful glimpse into the contemporary perceptions of children’s literature: many believed that reading, even in early childhood, should be a means to development; reading simply for enjoyment was frowned upon.

As Courtney Weikle-Mills argues in her essay, children’s literature was used by American publishers to promote patriotic ideals and shape the national identity in the wake of the American Revolution and the Civil War. This is clearly seen in attempts to claim Mother Goose as a national icon. Melodies for Children or Songs for the Nursery identifies Mother Goose as Elizabeth Vergoose and traces her family history from their arrival in Boston in the 17th century. Contrastingly, Jack Halyard and Ishmael Bardus in its dismissal of Mother Goose still plays into the patriotic narrative, describing the nursery rhymes as ‘made by ignorant people in England’. British editions of Mother Goose such as Mother Goose; Or, National Nursery Rhymes And Nursery Songs (1872) were no less patriotic, presenting the books as part of the ‘national song literature’ and offering them for use in the ‘great National Institutions’. Clearly, the patriotic publisher was a transatlantic phenomenon.

Primers, Family and Literary Legacies

Primers play a significant role in the early stages of teaching children to read, and there are over 200 examples to be found in the documents of Children’s Literature and Culture. They were originally designed to be purely instructional: textbooks created for the sole purpose of teaching the skill of reading. Early primers may contain lists of words or prayers, prioritising the value of raising responsible children with strong morals and virtue.

Primers play a significant role in the early stages of teaching children to read, and there are over 200 examples to be found in the documents of Children’s Literature and Culture. They were originally designed to be purely instructional: textbooks created for the sole purpose of teaching the skill of reading. Early primers may contain lists of words or prayers, prioritising the value of raising responsible children with strong morals and virtue. at the very centre of the tales within the book, offering a character to which the little reader can relate. The important relationship between animal depictions and human literacy, and their increasing prevalence in nineteenth-century alphabet books and children's narratives is expounded upon by Amy Ratelle in her essay.

at the very centre of the tales within the book, offering a character to which the little reader can relate. The important relationship between animal depictions and human literacy, and their increasing prevalence in nineteenth-century alphabet books and children's narratives is expounded upon by Amy Ratelle in her essay.